Quality Clicks with Kids

Publication: Look Magazine

Author: Christopher S. Wren

Photographer: Bob Lerner

Date: December 2, 1969

(Click images above for larger view)

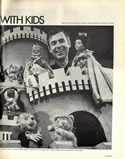

Hip parents spread the word: There's a television show that considers your child as worthwhile as you do. Instead of the usual cartoon mayhem, it creates drama from buttons, horseshoes and windmills. The weekday half hour is presided over not by some avuncular buffoon but by a family friend in coat and tie who is called Mister, and who seems to have stopped in on his way home from the office. He knows the most interesting people -- glassblowers, telephone repairmen, drummers, scuba divers. Even the puppets next door are literate and tuneful. And the show triggers no commercials at little minds.

Hip parents spread the word: There's a television show that considers your child as worthwhile as you do. Instead of the usual cartoon mayhem, it creates drama from buttons, horseshoes and windmills. The weekday half hour is presided over not by some avuncular buffoon but by a family friend in coat and tie who is called Mister, and who seems to have stopped in on his way home from the office. He knows the most interesting people -- glassblowers, telephone repairmen, drummers, scuba divers. Even the puppets next door are literate and tuneful. And the show triggers no commercials at little minds.

Misterogers' Neighborhood is a solid underground smash from a quiet channel -- public (formerly called educational) television. WGBH in Boston, the only public affiliate that troubled with an audit, found Misterogers' Neighborhood went into one out of three homes, wiping out the time-slot competition. In some cities, the Neighborhood is in such demand that it appears twice a day. At home in Pittsburgh, it is shown three times and is programmed into the curriculum of inner-city schools.

The Neighborhood supposedly draws  the three-to-seven-year-olds. In fact, the audience runs from toddlers to teenagers. Wry epigrams ("Anyone who thinks he'll always be first has a second thought coming.") keep a lot of mothers hooked. The wide appeal has prompted an evening family special on Monday, November 24 (Sunday, November 23 in the Northeast). Nighttime in Misterogers' Neighborhood will explore the fears and fancies that go on inside children's minds when the lights go out.

the three-to-seven-year-olds. In fact, the audience runs from toddlers to teenagers. Wry epigrams ("Anyone who thinks he'll always be first has a second thought coming.") keep a lot of mothers hooked. The wide appeal has prompted an evening family special on Monday, November 24 (Sunday, November 23 in the Northeast). Nighttime in Misterogers' Neighborhood will explore the fears and fancies that go on inside children's minds when the lights go out.

"I like you as you are / I wouldn't want to change you / Or even rearrange you / Not by far," a Neighborhood song tells young viewers. Children who have been taught they will be somebody only after piano lessons, school diplomas and a lot more birthdays get the message. The hub of Misterogers' Neighborhood is the dignity of the small.

"So many programs make children feel that if they don't know the alphabet or numbers, they don't have value," explains the Neighborhood's creator, writer, producer and -- at 41 -- oldest resident, Fred Rogers. "We have to let them know their worth comes from within."

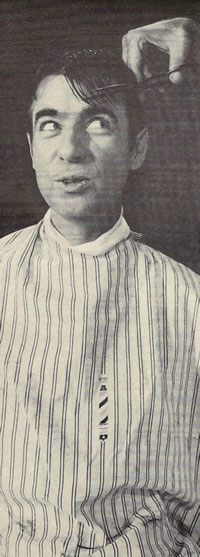

Off-camera, Fred Rogers might be overlooked in a small elevator. On-camera, Misterogers sparkles. Son of a factory owner in Latrobe, Pa., Rogers went off to Dartmough, chafed at the Ivy cheer and finished up a music major at Rollins College in Florida. He worked as an assistant producer for NBC in New York, but left after several years to help set up WQED, Pittsburgh's educational station. When there was no one else to do a children's program, he launched Children's Corner, with an initial budget of $30 a show. On the side, he went to Pittsburgh Theological Seminary. He was ordained a Presbyterian minister in 1962 and charged to work with children through TV.

Rogers went to Toronto with the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, where in 1963 he started Misterogers' Neighborhood. He brough it home to Pittsburgh two years later. After 100 shows it went broke and was rescued by a Sears-Roebuck Foundation grant and a children's fund from local TV affiliates, which pay an extra $100 weekly for the Neighborhood and a Canadian import, Friendly Giant. Each half-hour Neighborhood color show costs under $6,000 -- not quite enough, says Rogers, to produce two minutes of cartoons.

Rogers went to Toronto with the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, where in 1963 he started Misterogers' Neighborhood. He brough it home to Pittsburgh two years later. After 100 shows it went broke and was rescued by a Sears-Roebuck Foundation grant and a children's fund from local TV affiliates, which pay an extra $100 weekly for the Neighborhood and a Canadian import, Friendly Giant. Each half-hour Neighborhood color show costs under $6,000 -- not quite enough, says Rogers, to produce two minutes of cartoons.

He tees off at the "animated bombardment" of cartoons: "The whole thrust is to outwit what's big, that the child should do all he can to outwit the partent, and that this is the game of life. I don't think the people who program these things are vicious. They're just not aware. They've dipped into their unresolved childhood fears and spattered them all over the screen."

No one seems to care, and this appalls Rogers. "A lot of people use TV as a baby-sitter. You'd think if you wanted a baby-sitter, you'd try to get the best. You've bought a set and plunked it in the middle of your life. How is your child going to know you don't condone everything on that screen?"

Fred Rogers takes his responsibility so seriously that he tries to work stage directions left to right to encourage a young child's reading pattern. He tackles the problems grown-ups dismiss.  Misterogers proved to one audience they couldn't go down the bathtub drain. He has shown that haircuts and doctors' visits don't hurt, and plain-talked jealousy over a new baby. Rogers avoids violence, but not its consequences. After Rogers Kennedy was shot, he worked all night on a special program to make grief more comprehensive to children.

Misterogers proved to one audience they couldn't go down the bathtub drain. He has shown that haircuts and doctors' visits don't hurt, and plain-talked jealousy over a new baby. Rogers avoids violence, but not its consequences. After Rogers Kennedy was shot, he worked all night on a special program to make grief more comprehensive to children.

The whimsical still shines through. When he realized that busy parents always tell offspring to go play someplace else, Misterogers announced a new playground for puppets off-camera, duly named, of course, Someplace Else.

Misterogers' Neighborhood runs in two segments. The first is reality -- a visit with Misterogers and his friends in his home. The second is fantasy -- a visit to the neighborhood of Make Believe, populated by puppets with very human hang-ups. On his capable hands, they work out situations that a child himself might encounter. The dialogue, in Rogers' many voices, gets dotty. One chatty puppet advises another: "If at first you don't succeed, stay as sweet as you are." Misterogers keeps out of sight and always winds up the program back in the reality of his living room.

As Fred Rogers sees himself: "Before we got so mobile in this country, there was always a grandparent or an uncle who could give a child undivided attention. I think that I'm this adult male friend who stops in."

Some impressive friends come along with him. Van Clibrun played a command concert at the Make Believe castle. Metropolitan Opera baritone John Reardon devotes a week a year performing an opera with the puppets. Nightclub singer Mabel Mercer and Finian's Rainbow movie lead Don Francks have stopped by for a visit to Make Believe.

Some impressive friends come along with him. Van Clibrun played a command concert at the Make Believe castle. Metropolitan Opera baritone John Reardon devotes a week a year performing an opera with the puppets. Nightclub singer Mabel Mercer and Finian's Rainbow movie lead Don Francks have stopped by for a visit to Make Believe.

The show reflects early TV's informality, Rogers takes chances that would drive a commercial producer to another double martini. Betty Aberlin, the program's Bennington-educated ingenue, hit Pittsburgh with The Mad Show troupe and stayed to marry a doctor. When her pathologist husband hinted he wanted to visit the Neighborhood himself, Rogers wrote him in as a local wizard.

Fred Roger's home style runs to nothing fancier than high-calorie desserts. He lives quietly in a brick town house with his wife Joanne and sons James, 10, and John, 8. The Neighborhood is his life. During vacations, he blocks out the next season's 65 scripts in an old garage across the road from his gray-shingled summer home in Nantucket, writing after dinner into the night. He finishes them later in his weekend cottage near Pittsburgh, and talks them over with Dr. Margaret McFarland at the University of Pittsburgh's Arsenal Family and Children's Center. Eventually, he hopes to accumulate 780 color shows, enough for three straight seasons.

Rogers looks at himself as a teacher, not an actor: "I want to help children become antonomous. There is so much wasted energy in schools where conformity is the highest value. My great joy is to see what comes forth from a child who isn't shackled. The joy should not have been pounded out of learning."

If he is successful, he says, the audience will outgrow him. "By the time a child is in the second grade, he can set our program aside. If we help him resolve his normal feelings, he can be much freer to learn in school." Nonetheless, his audience keeps hanging around.

"By the time a child is in the second grade, he can set our program aside. If we help him resolve his normal feelings, he can be much freer to learn in school." Nonetheless, his audience keeps hanging around.

Fred Rogers hasn't seriously considered a shift to the more profitable commercial networks: "I'm afraid my stipulations would be too great. When you do what you know you should be doing, being famous isn't important anymore."

Misterogers not famous? In Los Angeles, over 6,000 children showed up at the modest UHF station when he visited; thousands more were turned away. (He saw the arrivals, 275 at a time) The Boston station can't invite him because it couldn't handle the crowds. His records sold out within days after they appeared last Christmas. When he testified at last May's Senate hearings, he was even spontaneously endorsed by TV's task-master, Sen. John Pastore.

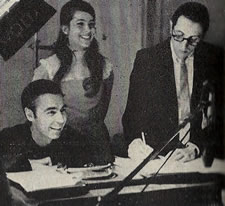

Johnny Costa, jazz-seasoned musical director of the Neighborhood, rejected a lucrative network-TV offer so he could stay in Pittsburgh with Misterogers. Of his boss, he suggests: "Grown-ups say to kids, 'Get out of my way. I've got important things to do.' Here's a man who cares, and these kids know it. He says, 'You're you, and you're worth something.'"

Some of the fantasy he has spun is bound to stick to the diffident Fred Rogers. In New York last spring to receive broadcasting's Peabody Award, he stopped in the Pierre Hotel lobby by a small boy who inquired: "How did you get out of the TV set Misterogers?" Rogerst ook a few minutes to explain that what was in the tube was really just a picture. At last, the boy nodded, and asked: "How are you going to get back in the set, Misterogers?"